Injury from a light show laser?

Every few years, ILDA receives a report of a claimed or suspected eye injury to a laser light show audience member.

It is theoretically possible for such an injury to occur. After all, in almost 40 years of widespread laser shows, 140 million people have had 14 billion exposures of laser light in their eyes. And unfortunately many of these exposures were well over the Maximum Permissible Exposure levels that safety experts recommend.

Despite all this, in all those years there has been literally just a handful of claimed or suspected eye injuries from continuous-wave visible light lasers used for shows. A number of reasons that actual injuries are so low are listed below.

Because of this record of few injuries, we urge doctors, media, regulators and others to use caution when there is a claim of an eye injury. Is it really a laser injury? If so, was it really caused by a laser light show laser laser?

Again, it is theoretically possible for someone to suffer an injury from a continuous-wave visible light laser show … but review the information below before coming to any final conclusion:

-

Self-inflicted injuries

Some claims of injury are found to be (unfortunately) self-inflicted.

For example, some people have had corneal injuries which they said were caused by a laser beam.

However, a visible-light laser beam like those used at discos and laser shows, goes completely through the cornea, which is transparent. Being transparent, the cornea cannot absorb energy from the laser beam. In other words, a visible-light laser beam cannot cause a corneal injury.

What is always found is that the person rubbed their eye too hard. This can cause painful corneal scratching. Fortunately, the cornea can heal from this.

Another example of self-inflicted injury comes from a 1990s case where an disco patron deliberately stared into a laser beam, and reported a 75% loss of vision in one eye.-

Pre-existing problems

Some claims of injury are due to pre-existing problems which the affected person perhaps did not notice until having bright laser beams in their eye. After the show, they look more carefully and see a spot or other problem.

Of course, the laser did not cause the pre-existing problem.

For example, there have been at least two cases of pilots, claiming injury from laser pointers, who had real problems in their eyes. After examination by laser injury specialists, the problems were not found to be caused by the reported laser exposures.-

Laser pointers in the crowd

Some claims of injury are partially correct -- a laser at a show caused a retinal injury -- but it was not the show laser but instead laser pointers used by crowd members.

In a 2009 case, two people at the "Tomorrowland Festival" in Belgium were injured by misuse of laser pointers that were in the audience. This case is discussed here.-

Using the wrong type of laser

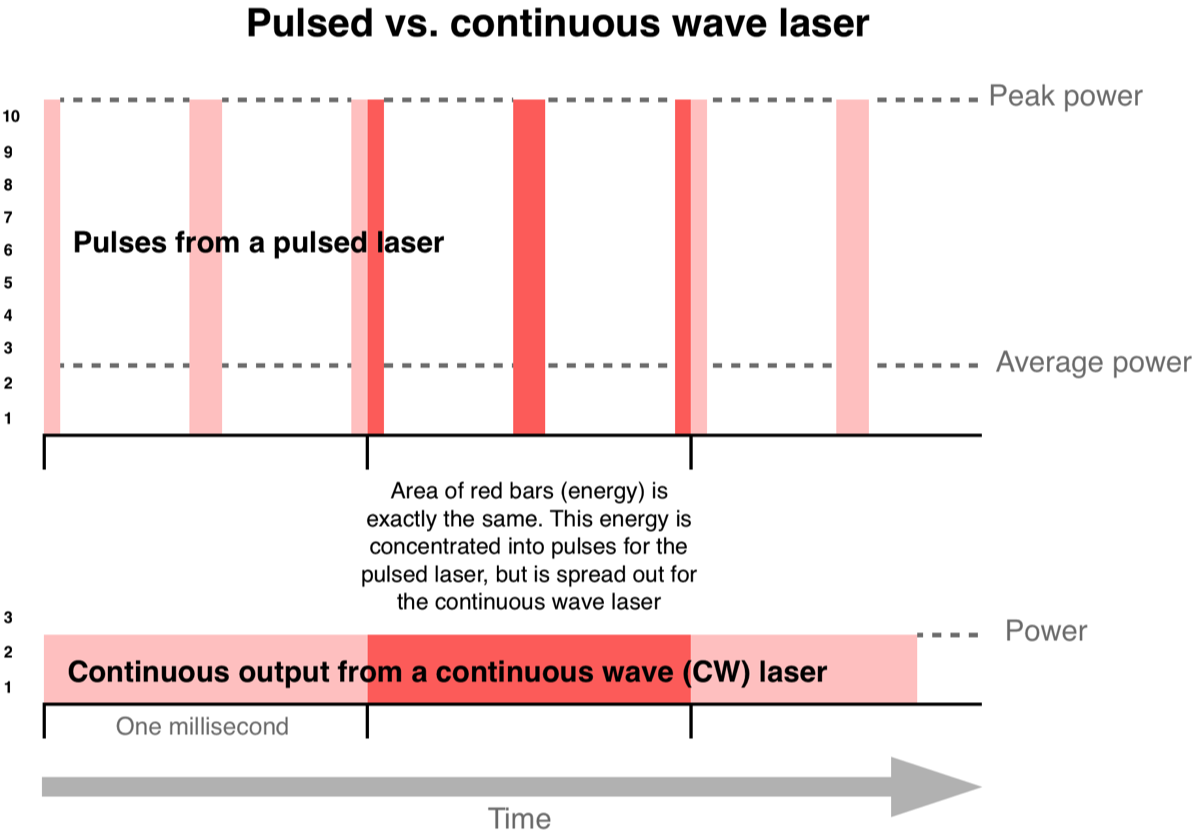

There have been some cases of injury caused by using a certain type of laser incorrectly. This is when a pulsed laser is aimed into a crowd to do audience scanning.

Pulsed lasers are inherently MUCH more dangerous than normal continuous wave lasers. Each pulse carries much more energy than the continuous stream of normal laser light, as shown below.In July 2008 approximately 35 people in Russia suffered eye injuries when a pulsed laser, planned to aim safely into the sky, was instead dangerously aimed into the crowd. This case is discussed here.

The International Laser Display Association has strict rules and warnings that audience scanning is NEVER to be done with pulsed lasers. See item 9 in the list of Lasershow Safety - Basic Principles.

In all of ILDA’s information about laser shows and audience scanning, it is assumed that only continuous wave visible-light lasers are being used, unless otherwise specifically noted.

And when we discuss injuries from audience scanning, ILDA is counting only those involving CW visible lasers. This is because pulsed lasers should NEVER be used for audience scanning. Such injuries are due to misuse of pulsed lasers, not anything inherent to CW visible laser audience scanning.-

Reasons actual injuries are so low

Below are some reasons that, despite 140 million people having 14 billion exposures of continuous-wave visible laser light in their eyes, the number of documented injuries from such exposures appears to be in the single digits.

MPEs have a built-in safety factor

The Maximum Permissible Exposure is set roughly 10 times below the level at which there is a 50/50 chance of an exposure causing the smallest visually detectable change to the retina, under laboratory conditions where both the laser and the eye are immobile.

Here is another way to say this. If a non-moving laser beam having an irradiance 10 times the MPE were to be aimed into an audience member’s completely dark adapted eye (pupil at 7 mm), there would be only about a 50% chance that the smallest detectable change to the retina would occur. Such a minor injury would likely heal in the same way that a small scratch or burn to the skin heals.MPEs have an even higher safety factor to prevent noticeable injuries

MPE irradiance levels are intended by definition to prevent changes to the eye. These changes may only be detected during an eye exam, or by laboratory tests under controlled pre- and post-exposure conditions. It would take even higher irradiance levels to cause spots or vision problems which a person would notice on their own, in their everyday life.

This raises the possibility that laser shows over the MPE may, theoretically, be causing changes in some eyes (detectable with careful examination) but are not so far over the MPE as to cause noticeable or reportable vision problems.Viewers are not always looking at the laser source

In a disco or concert situation, the focus is not usually exclusively at the laser source. Therefore, laser light will either miss those looking away from the source, or will enter the eye at an oblique angle and be focused on the periphery of vision.

Aversion response helps avoid serious injuries

The natural aversion response to bright light causes viewers to blink and/or move their head if light entering the eye is too bright. This reduces the potential harm from exposures longer than the nominal 1/4 second aversion response time.

Avoidance response helps avoid minor injuries

In addition to the sudden aversion response, viewers also take more subtle, often subconscious avoidance actions if the light is too bright. This has been routinely observed at shows with bright lasers. As an effect is about to cross a viewer’s face, they will move their head slightly, glance down, squint and/or blink.

Blocking the beam avoids any exposure

We have seen viewers deliberately position themselves so that another person’s head, a column, or a similar obstacle blocks the direct beams coming from the projector. In such a case, most of the show can still be enjoyed.

Less light is entering the eye than standards anticipate

Laser safety standards are based upon a dark-adapted pupil size of 7 mm. But most displays are not viewed as a single beam in total darkness. With additional stage lighting, shows are often quite bright. This constricts the pupil, making a pupil size of 4-5 mm more likely.

At 5 mm, the pupil lets in only about 50% as much light as a 7 mm pupil, and the pulse width of a scanned beam crossing the pupil is decreased by 30%. Both factors lead to a significant hazard reduction.The pupil is relatively far from the laser source

In laboratory and industrial accidents, the pupil is often within a meter or two of where the laser beam emerged or was reflected from. However, in most laser light show displays the audience is much further away from the laser source or a bounce mirror. This gives the beam more room to diverge.

There is a small chance of hitting a pupil

In cases of accidents or poor design where a powerful static (non-moving) beam may stay fixed for many seconds, there is a small chances of hitting a person’s pupil.

For example, the total pupil area of 100 persons in a nightclub (scan field of 10 x 10 meters) is roughly 1/25000 of the total area scanned by the laser. Any randomly positioned beam would have a 1/25000 chance of directly hitting a pupil.Only part of the audience is closest to the laser

The MPE is calculated for the closest audience members. However, most viewers are farther away. They receive less light energy for two reasons: 1) the beam diverges more and 2) the linear velocity of a scanned beam increases with distance.

Depending on the crowd depth, the beam power may be significantly reduced for audience members who are not in front.Theatrical fog and haze weakens the beam

Theatrical fog and haze are often used at laser light shows. These help increase the visibility of the beam. (In completely clear air, there are no particles for the light beam to reflect off so it has low or no visibility.)

The laser light is scattered and dimmed by particles in the air. This can substantially reduce the amount of laser power that reaches the eye. This power reduction is stronger the further the beam travels — the more fog or haze the beam encounters.-

Enter title here

If you believe you were injured by a laser — from a show, from laser pointer misuse, or from some other cause — see this webpage about what to do if you are hit by a laser beam.

If the potential injury is from a laser show, also please contact ILDA. We will add this to our list of known injury reports. We will also take any appropriate steps to investigate and, if it is a Member, take action within ILDA.-

Enter title here

Detailed information about audience scanning injuries, potential reasons for the low rate of reported injuries, and related information is in a 31-page paper, “Scanning Audiences at Laser Shows: Theory, Practice and a Proposal.” This paper was originally presented at the 2009 International Laser Safety Conference. It has been updated as of 2012.

If you believe you were injured

If the potential injury is from a laser show, also please contact ILDA. We will add this to our list of known injury reports. We will also take any appropriate steps to investigate and, if it is a Member, take action within ILDA.

For more details

For more information, visit our other ILDA websites:

© 2007-2026 International Laser Display Association. All rights reserved.

Contact ILDA

No reproduction of the text or images on ILDA websites is allowed without written permission of ILDA or other copyright holders. "ILDA" and the ILDA logo are trademarks of the International Laser Display Association.

This site does not use cookies and does not track or gather information on individual visitors. Aggregate information is gathered by Google Analytics to determine overall visitor behavior. More information is on our Privacy Policy page.